The Spanish colonisation of South America is well documented in history. By the middle the late 16th century the empire of Spain had established as many as 30 separate colonies and 10 major cities in the new world, giving them a strong foothold from which to exert their cultural, political, militaristic, linguistic, and, of course, religious dominance.

With regard to the latter, the remnants of Spanish missionary culture in the Jesuit order are peppered all over the place, through Brazil, Argentina and through Bolivia in the east. But the first instances of this Spanish strategy of Jesuit conversation are generally accepted to have taken place in the sparse Guarani rainforests in the south central region of the continent; in other words, modern day Paraguay.

Today, two of the most striking remnants of the Spanish reductions in Paraguay are also two of the country’s most visited cultural and historical sites. Both were inaugurated into the UNESCO world heritage list simultaneously in 1993, toted as the finest reminders of ‘the Jesuits’ Christianization of the Río de la Plata basin… [and] the accompanying social and economic initiatives” that went with it. Indeed, the historical importance of the Jesuit missions in Paraguay cannot be overstated; the religiously motivated social projects that emanated from these two sites were integral to the development of the dramatic story of this country’s people, from the 16th century to modernity.

At the heart of the Jesuit missionary vision was a rejuvenation of the natives’ social order, which with the onslaught of Spanish militarism and colonialist economy had been threatened by the ‘encomienda’ legal system, an organisation of pseudo-slavery which reduced the native tribes of Paraguay to commodities of the Spanish land owners.

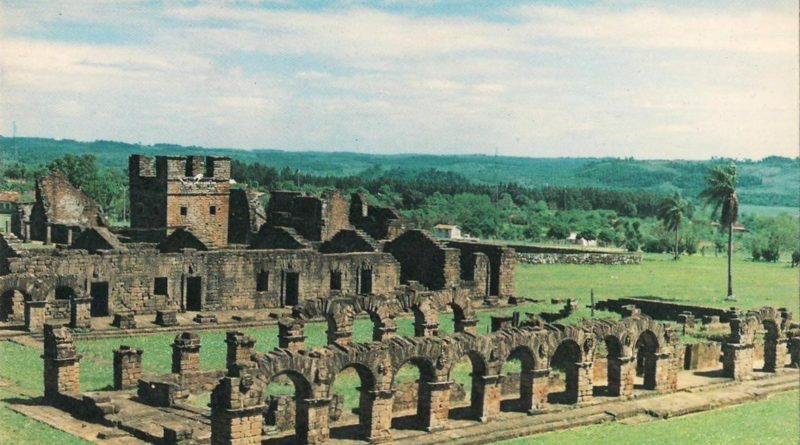

It’s easy to see how conversion would have offered a welcome out. In exchange for a brutal Spanish slave-driver, the Jesuits would offer schooling; language classes and practical workshops that helped transmit the technology of the empire to the new world. At both of the sites in Paraguay, the ruined walls of the educational sections of the missionary complexes are still viewable; utilitarian rectangular structures adjoined by courtyards to the undisputed centrepiece of it all: The cathedral.

At the Jesus mission the central church is a hodgepodge of various architectural styles, all unashamedly European. From the Romanesque decorations on the doorway apses, to the Renaissance colonnades that structure the outside, this building was one of the first examples of these altogether new influences and art forms in South America; particularly apt for a building meant to popularise the ideas of a religion so alien to the indigenous peoples of Paraguay.

However, there are also some thought-provoking examples of cross culture architecture at the sites, where the dominant European styles adopt something of a Guarani flavour. In fact it’s this two-way cultural moulding of the buildings, their art, and maybe even the ideas they harboured, that made the Jesus and Trinidad Jesuit Missions of Paraguay such an obvious choice for UNESCO inauguration.

Just over 7 miles down the road from the Jesus mission, the Trinidad mission dates from 1706, some 21 years after the completion of its nearby counterpart. Here the usual pattern of layout is followed, with the central church dividing the two living areas, the tribal natives on the one side and the Jesuit missionaries themselves on the other. However Trinidad differs from many of the other reductions in the countries of South America, by the conspicuous existence of two churches on the same site.

This additional church is usually mentioned as the Pièce de résistance of both missions. Its fantastic doorways and red-brick frontispieces have survived fully intact, while the artistic decorations are prime examples of the cross-culture heritage that was to become the roots of modern Paraguayan and other national identities.

At Trinidad too, there’s a series of well-preserved wall adornments and sculpture that indicative of the Spanish colonial and Jesuit art of the period. What’s more visitors can still see the crypt and holy water font that were integral parts of the church in the 17th century.

Most visitors to the sites can’t help but notice the lack of crowds, and it’s true that this is one of the truly deserving UNESCO spots that don’t have the hubbub that usually comes with the epithet. That said, these are open and large areas where there’s plenty of room for crowds to disperse and scatter, so it may be just a case of ‘what one can’t notice’. Entrance fee is a nominal 5000 guaranis per person, and most tours from both Encarnación and the Argentinian border will make use of a public bus that can take up to 7 hours.